Writings

Selected Stories

Stage Fright (Valparaiso Fiction Review)

Julia splurged on a bucket-shop, round-the-world ticket, a month of travel between leaving San Francisco and landing in New York to start rehearsals. She’d be spending everything she had on the trip, with just enough left to get a cheap place to live in New York. Her older brother Robert was furious with her, first of all for leaving their own company, but also, apparently, on behalf of the honor of experimental dance-theater in general. He said, “You have some idea that doing Shaw in New York will make you a real actress. You’re a real actress here, even if it’s not all talk-talk-talk. But fine, go for a year. You’re going to hate all that artifice and clawing for position. Just let me know when you’re ready to come home.”

News of the World (Ploughshares)

We were the News-of-the-World Theater Collective, moving from city to city together; we were all married to each other and to the idea of what you could pull from the streams of the news that ran over and around and through our lives. We wanted no one to let that information splash over them without thinking, so much unnoticed linguistic and conceptual sewage. Selene and I were with the company for six years – in the Tenderloin, in various U.S. cities during the year when we were touring by bus, and then back home in San Francisco, where it all broke apart for us.

Rising with the Seas (Image)

First come the fires, the neglected grid breaking down and sparking the dry fields. Next a week of clouds, so dark, so heavy, like nothing we’ve ever seen. Methuselah’s death has put all the humans in a panic. They miscounted the days; they thought the rains would start later, much later, or perhaps would never come. The future is here; this is that very moment. I run down the streets, looking for my sister, my twin, Azy, who’s broken out of our pen again. Restless Azy, perfect in a way I have never wanted to be. I am always afraid for her.

Invisible Theater (Scoundrel Time)

Not long after the Loma Prieta earthquake, our collective decided to stage an Invisible Theater performance in the atrium restaurant of a grand hotel in San Francisco’s Financial District. When Eva and I walked in, she nodded to our brother Robert, who was sitting forward in his seat several tables away and lit up with pre-show adrenalin. He pretended not to see us. Eva, who’d never been at one of our disruptions, gave an annoyed shrug. I tried to avoid exchanging looks with the Electric Disciples scattered throughout the room, nursing cups of soup or the cheapest possible drinks. Not all of us were performing tonight, but we were there to support each other in case we were needed.

Sarah’s Blessings (Or, Is There Such a Thing as Inappropriate Laughter) (Image)

We can’t imagine that anyone can believe God announcing a miracle. Most miracles are hilarious. Abraham threw himself on his face and laughed, as he said to himself, “Can a child be born to a man one hundred years old, or can Sarah bear a child at ninety?” It was Ishmael he was worried about, Hagar’s child playing by the water, not yet the father of twelve chieftains but the kid who made boats of bark and hid when he was called in to dinner.

Earthly Delights (Image)

Tigers nuzzling antelopes. Ocelots and lemurs napping. Small cats picking their way along the riverbank. The moss smells of morning and memory; water curls under and around the trees. A shimmer of wind on fur, first drops of rain falling.

He wakes and moves through the garden, dazed, surrounded by the animals, who may or may not be paying any attention to him.

“Hiding Places” and “The Dinner Guest” (LEON Literary Review)

At dinner, my friend says that her favorite game as a child was running away and hiding. She would get the other children to find a place they could be safe. We’d been talking about how old we were when we first learned our family histories. Her family, considering the neighbors, asked, who would hide us?

Sylvia Fein, Musical Sky Eyes

Three Stories Inspired by Sylvia Fein Paintings (100 Word Story)

From the site: “In honor of ‘Midwest Surrealist’ Sylvia Fein’s 100th birthday, the Berkeley Art Museum put on an exhibition of Fein’s work, exploring such characteristic themes and motifs as water, trees, eyes, cats, and the cosmos. “Three Bay Area writers, Ron Nyren, Maw Shein Win, and Sarah Stone wrote 100-word stories inspired by Fein’s fantastical imagery. And Evan Karp scored each of their readings to his own musical interpretations of the stories and the paintings.” See, and hear, the paintings, stories, and Evan’s scores here.

Selected Essays, Reviews, and Interviews

Mystery vs. Confusion (CRAFT)

Self-Awareness & Self-Deception: Beyond the Unreliable Narrator (A Kite in the Wind: Fiction Writers on Their Craft, anthology, Trinity University Press, also in The Writer’s Chronicle)

Research Notes for Hungry Ghost Theater (Necessary Fiction)

Politics and the Imagination: How to Get Away with Just about Anything (in Ten Not-So-Easy Lessons) (Included in the anthology Dedicated to the People of Darfur: Writings on Fear, Risk, and Hope, Rutgers University Press, also appeared in The Writer’s Chronicle)

The Pleasures of Hell (The Writer’s Chronicle)

Teeming with Villains & Villainesses, or, Taking Sides (The Writer’s Chronicle)

Transforming the Agenda (The Writer’s Spotlight)

How We Spend Our Days (Catching Days series)

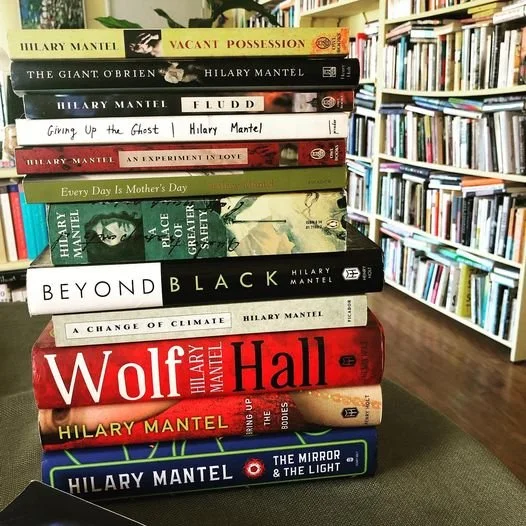

Hilary Mantel, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher (Review, San Francisco Chronicle)

‘Only Because It’s Forbidden’: Seduction and Loss in Jessica Hagedorn’s The Gangster of Love (Alta Journal online for the California Book Club)

‘Consciousness, Splintered,’ Venita Blackburn’s Dead in Long Beach, California (Alta Journal online for the California Book Club):

Cristina Henríquez, Book of Unknown Americans (Review, San Francisco Chronicle)

Edan Lepucki, California (Review, San Francisco Chronicle)

A Classic Nightmare: On Emily Fridlund’s History of Wolves (Review, The Millions)

Sylvia Brownrigg (Interview, Necessary Fiction)

Joan Silber (Interview, The Believer)

Anita Felicelli (Interview, Full Stop)

Dubravka Ugresic, The Ministry of Pain (Review, The Believer)

Stacey D'Erasmo, Blood, Breath, Bone, String: A Seahorse Year (Review, The Believer)