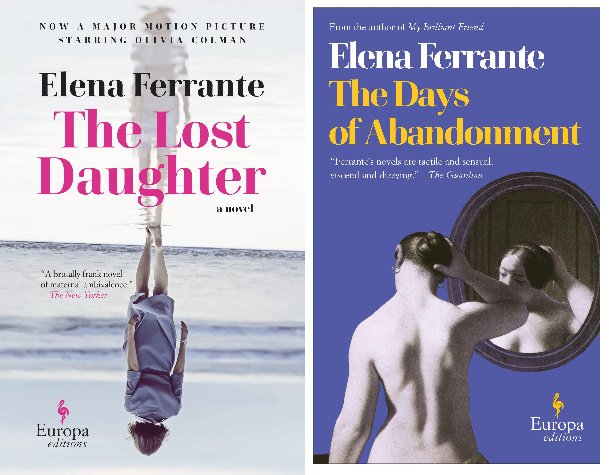

Elena Ferrante, Days of Abandonment and The Lost Daughter: Hypnotic Intensity

/The first time I tried to watch the movie version of The Lost Daughter, I stopped about a quarter of the way through: the level of emotion felt unendurable. I’ve since talked to at least a couple of friends who stopped and never went back. But I couldn’t get it out of my mind, so I read the novel, took a week or so to recover, then watched the rest of the film. Both versions still recur to me, a few months later, and with so much happening in life and in the world, I wondered what makes them so hypnotic, how they can feel so strange and dreamlike (full of actions no reasonable person would take) but also touch home for so many of us."

In Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter (La figlia oscura, Ann Goldstein, translator), Leda, a middle-aged scholar and teacher on a working vacation by the sea, becomes involved with a young family. They are from Naples and fascinate and repel her, representing everything she’s fled. Most of all, she becomes attached to Nina and Elena, a beautiful young mother and daughter. And then she secretly steals the child’s doll, wreaking havoc but stubbornly holding onto the toy even as Elena cannot be calmed, runs a fever, doesn’t sleep. Leda’s also possessed by her own memories of being an unhappy daughter and then later a young mother who could not find a way to reconcile her ambition and passion for work with the constant demands of mothering. In the movie version, despite the beauty of the acting and directing, I missed Ferrante’s multiple layers of mother-daughter-mother resonances and memories. And missed what it meant for Leda to be from Naples, for the family to remind her of everyone she’d escaped.

The emotional intensity and interiority create a hypnotic effect, maybe in part because the interiority moves the plot forward. Though she doesn’t actually speak to them here, we can feel that she’s going to take some unsettlng or unwise action. Here’s a whole sequence of Leda’s response to Nina and Elena’s relationship around the doll she’ll wind up cruelly stealing, her jealousy and irritation, as she watches the beautiful young mother and daughter. So much tension here comes from the psychologically intricate but clear and specific prose, the mixture of observation and emotion, the growing internal struggle that Leda feels in watching the family:

Nearly a week of vacation had already slipped away: good weather, a light breeze, a lot of empty umbrellas, cadences of dialects from all over Italy mixed with the local dialect and the languages of a few foreigners who had come for the sun.

Then it was Saturday, and the beach grew crowded. My patch of sun and shade was besieged by coolers, pails, shovels, plastic water wings and floats, racquets. I gave up reading and searched the crowd for Nina and Elena as if they were a show, to help pass the time.

I had a hard time finding them; I saw that they had dragged their lounge chair closer to the water. Nina was lying on her stomach, in the sun, and beside her, in the same position, it seemed to me, was the doll. The child, on the other hand, had gone to the water’s edge with a yellow plastic watering can, filled it with water, and, holding it with both hands because of the weight, puffing and laughing, returned to her mother to water her body and mitigate the sun’s heat. When the watering can was empty, she went to fill it again, same route, same effort, same game.

Maybe I had slept badly, maybe some unpleasant thought had passed through my head that I was unaware of; certainly, seeing them that morning I felt irritated. Elena, for example, seemed to me obtusely methodical: first she watered her mother’s ankles, then the doll’s, she asked both if that was enough, both said no, she went off again. Nina, on the other hand, seemed to me affected: she mewed with pleasure, repeated the mewing in a different tone, as if it were coming from the doll’s mouth, and then sighed, again, again. I suspected that she was playing her role of beautiful young mother not for love of her daughter but for us, the crowd on the beach, all of us, male and female, young and old.

The sprinkling of her body and the doll’s went on for a long time. She became shiny with water, the luminous needles sprayed by the watering can wet her hair, too, which stuck to her head and forehead. Nani or Nile or Nena, the doll, was soaked with the same perseverance, but she absorbed less water, and so it dripped from the blue plastic of the lounger onto the sand, darkening it.

I stared at the child in her coming and going and I don’t know what bothered me, the game with the water, perhaps, or Nina flaunting her pleasure in the sun. Or the voices, yes, especially the voices that mother and daughter attributed to the doll. Now they gave her words in turn, now together, superimposing the adult’s fake-child voice and the child’s fake-adult voice. They imagined it was the same, single voice coming from the same throat of a thing in reality mute. But evidently I couldn’t enter into their illusion, I felt a growing repulsion for that double voice. Of course, there I was, at a distance, what did it matter to me, I could follow the game or ignore it, it was only a pastime. But no, I felt an unease as if faced with a thing done badly, as if a part of me were insisting, absurdly, that they should make up their minds, give the doll a stable, constant voice, either that of the mother or that of the daughter, and stop pretending that they were the same.

It was like a slight twinge that, as you keep thinking about it, becomes an unbearable pain. I was beginning to feel exasperated. At a certain point I wanted to get up, make my way obliquely over to the lounge chair where they were playing, and, stopping there, say That’s enough, you don’t know how to play, stop it. With that intention I even left my place, I couldn’t bear it any longer. Naturally I said nothing, I went by looking straight ahead. I thought: it’s too hot, I’ve always hated crowded places, everyone talking with the same modulated sounds, moving for the same reasons, doing the same things. I blamed the weekend beach for my sudden attack of nerves and went to stick my feet in the water.

Ferrante’s writing here has the quality of exact, bemused observation, both of the actions of Elena and Nina and of Leda’s own emotions. Leda seems to be a spectator of a part of herself she has no control over, even as she’s overly emotionally involved with this pair she hardly knows.

The narrative question here seems to be “what is she going to do about this irritation?” She herself doesn’t know, can’t anticipate it. It’s not just Nina’s performative willingness to endure the endless sprinkling or the annoying voices. Leda’s furious at this merging of mother and daughter, when she has had such distances and discords with her own mother and daughters. These two in front of her “don’t know how to play.” All this is submerged: she doesn’t have the self-awareness to point it out, even though she can create an exact topography of her feelings. A reader who’s paying attention (or perhaps rereading!) can see what’s happening to her, but the passage doesn’t do the work for us.

By stealing the doll, she can disrupt the unnervingly close mother-daughter bond. To make them more like herself and so diminish her feeling of being left out? Because she’s envious? This level of motivation stays open.

The Lost Daughter reminds me of a slightly earlier book of Ferrante’s, Days of Abandonment, a deeply emotional story of a woman undone by being left by her husband, the story of how she grapples with it and the changes she goes through. Ferrante makes all this high emotion readable by refraining from deliberately whipping up the reader’s own emotions. She doesn’t ask us to over-identify with the narrator. But at the same time, she’s not downplaying the devastation the character feels. Here’s another sequence of paragraphs, the beginning of this book:

One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator. He told me that he was confused, that he was having terrible moments of weariness, of dissatisfaction, perhaps of cowardice. He talked for a long time about our fifteen years of marriage, about the children, and admitted that he had nothing to reproach us with, neither them nor me. He was composed, as always, apart from an extravagant gesture of his right hand when he explained to me, with a childish frown, that soft voices, a sort of whispering, were urging him elsewhere. Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the front door carefully behind him, leaving me turned to stone beside the sink.

I spent the night thinking, desolate in the big double bed. No matter how much I examined and reexamined the recent phases of our relationship, I could find no real signs of crisis. I knew him well, I was aware that he was a man of quiet feelings, the house and our family rituals were indispensable to him. We talked about everything, we still liked to hug and kiss each other, sometimes he was so funny he could make me laugh until I cried. It seemed to me impossible that he should truly want to leave. When I recalled that he hadn’t taken any of the things that were important to him, and had even neglected to say goodbye to the children, I felt certain that it wasn’t serious. He was going through one of those moments that you read about in books, when a character reacts in an unexpectedly extreme way to the normal discontents of living.

After all, it had happened before: the time and the details came to mind as I tossed and turned in the bed. Many years earlier, when we had been together for only six months, he had said, just after a kiss, that he would rather not see me anymore. I was in love with him: as I listened, my veins contracted, my skin froze. I was cold, he was gone, I stood at the stone parapet below Sant’Elmo looking at the faded city, the sea. But five days later he telephoned me in embarrassment, justified himself, said that there had come upon him a sudden absence of sense. The phrase made an impression on me, and I had turned it over and over in my mind.

Ferrante doesn’t give us the scene, or any of the details of what the husband says, apart from his magnanimous willingness to take all the blame and his apparent reference to “soft voices urging him elsewhere.” If that were dialogue, it would be impossible. Can we accept the interpretation as accurate at all? Did our narrator respond? We have no idea. Instead, as if in a daze, “turned to stone,” she focuses on the “extravagant gesture of his right hand” his “childish frown.” Again, as with Leda watching the mother and daughter, she sees something performative here.

She doesn’t take him seriously, as she says in the next paragraph. She has no sense of a need for change, either in him or herself. She’s not trying to get him help with those voices. And she’s not coming up with a plan for them to get counseling, pleading her case in her own mind, discovering reasons. Were they contemptuous or defensive with each other? Apparently not. They “talked about everything…still liked to hug and kiss each other” and sometimes “he was so funny he could make me laugh until I cried.” The husband “assumed the blame for everything that was happening” and left.

In the third paragraph, she adds the information that it happened before, one reason she’s not taking him seriously now, awful as it had been at the time. He had “a sudden absence of sense.” So she thinks it’s all going to be fine. But the book is called Days of Abandonment (I giorni dell abbandono). Perhaps it will be fine in some sense, down the road, but in the meantime, we’re in for an emotional journey.

Ferrante (whoever she or they may be – there are links at the bottom of these notes for anyone who hasn’t delved into this question and would like to) keeps writing about the pressures of motherhood, the merging, the demands, the assumptions. In Days of Abandonment, the only mention so far of the rest of the household is “the children…quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog…dreaming, growling beside the radiator.” The husband can come and go as he pleases, apparently without the terrible divisions and guilt Leda felt in The Lost Daughter when she left her own children for a period of time. Here, the husband doesn’t even say good-bye to his children. It’s understood that, whatever our narrator is going through, she’ll need to rise to looking after them. It goes without saying.

As with The Lost Daughter, there’s a sense of loaded, slow-building trouble ahead. Both novels have reasonably unreasonable narrators, with their careful but possibly mistaken and certainly biased assessments of their situations. Not unreliable in the traditional sense (no one is a serial killer trying to convince us of their innocence, no one is lying to the reader in a deliberate way), but also not completely reliable. They are highly aware of other characters, but as if through a filter. Their insights and discoveries are intriguing, puzzling, frustrating. We see a little beyond what they seem to see, but despite the very specific observation, we’re not always sure of either their perceptions or our own.

* * *

Ferrante links:

https://lithub.com/have-italian-scholars-figured-out-the-identity-of-elena-ferrante/

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/12/elena-ferrante-pseudonym/573952/

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/09/books/review/ties-domenico-starnone-jhumpa-lahiri.html