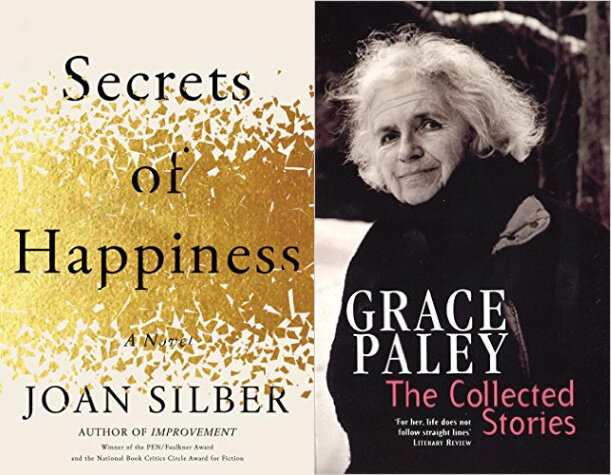

Joan Silber on Grace Paley's "Mother" and "A Conversation with My Father"

/(Guest post by Joan Silber)

Grace Paley was my teacher, senior year at Sarah Lawrence. People have asked me ever since what she taught me, and I don’t know that I’ve ever answered this right. What I’ve said is true: she told us fiction was all about character, she emphasized voice, and I once heard her say she could write stories when she understood they could be organized like poems. This last bit made perfect sense to me at the time—story as a pattern of emotion—though people are confused when I say it now. I wanted to be a poet then—it was a mixed genre class—and Grace’s first fiction assignment for me was to write in the point of view of someone I was not in sympathy with. She may have gotten this from someone else—it was her first year teaching and it’s a pretty common assignment—but I still take to heart the impulse behind it. (In fact, I saw now, when I was looking again at her three books, that Mrs. Rafferty, who’s a pain in the ass in a story in the first book, has her own story in the second. How could I not have remembered that? I who do that all the time.)

But, really, what she taught the most thoroughly was the need for vividness—I know this is a vague term, but she applauded the moments when characters fully animated the prose, when their hidden energies and unforced capacity for eloquence took over. Here is the opening to “Mother,” from her last book, Later the Same Day:

One day I was listening to the AM radio. I heard a song: “Oh, I Long to See My Mother in the Doorway.” By God! I said, I understand that song. I have often longed to see my mother in the doorway. As a matter of fact, she did stand frequently in various doorways looking at me. She stood one day, just so, at the front door; the darkness of the hallway behind her. It was New Year’s Day. She said sadly, If you come home at 4 a.m. when you’re seventeen, what time will you come home when you’re twenty? She asked this question without humor or meanness. She had begun her worried preparations for death. She would not be present, she thought, when I was twenty. So she wondered.

The vividness in this is also charged by its use of time (ever important to me). The narrator is remembering from a long span back—the intensity of emotion is accompanied by the distance time affords. The events have been survived.

Her most famous story, “A Conversation with My Father,” from Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, has its own great ironies about time. The narrator tells a story to her aging father about a woman in the neighborhood whose teenage son became a junkie. To stay close, the mother joined him in his habit, and was left behind when he stopped using. The narrator’s father thinks the woman is hopeless, but another ending is supplied, archly but sincerely:

Of course, her son never came home again. But right now, she’s the receptionist in a storefront clinic in the East Village. Most of the customers are young people, some old friends. The head doctor has said to her, “If we only had three people in this clinic with your experiences…”

Reading this of course makes me feel how much I bear her mark. I’ve written any number of stories where characters step from one life to another.

Here’s a paragraph from my new book, Secrets of Happiness, in which I now see traces of Grace’s methods of telling:

My brother’s longtime boyfriend decided to leave him, once and for all. Enough, he said, was enough. If you can’t stop arguing after twenty years, when will you ever? Time for a new start for both of them. They would always be friends, of course. He would always care about Saul, but he did not think that waking up every day in the apartment was good for either of them

This speech might have made sense except that my brother had just been diagnosed with some stage or other of leukemia.

In the summer of 2018, after my book Improvement was out, I was invited to read in New Hampshire. The bus ride from Manhattan took hours longer than it was supposed to, and I naturally thought, why am I doing this? Once I got there, everything was great—my host had built a Japanese garden in his yard and we swam in a pond with the dog, I read with a terrific poet (Lloyd Schwartz), and on the ride back to my lodging afterward, I got to talk to Nora Paley, Grace’s daughter, who lived nearby. Nora said to me, “I heard the ghost of my mother in what you read.” And all I could think was, I would have walked all the way from New York for days and days to hear that.

Photo credit: Shari Diamond

Joan Silber is the author of nine books of fiction. Her novel, Secrets of Happiness, will be published by Counterpoint on May 4, 2021. Her last book, Improvement, won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the PEN/Faulkner Award, and she received the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story. Her book Fools was longlisted for the National Book Award and a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award; The Size of the World was a finalist for the LA Times Fiction Prize; and Ideas of Heaven was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Story Prize. She lives in New York, taught for many years at Sarah Lawrence College, and teaches in the Warren Wilson MFA Program.