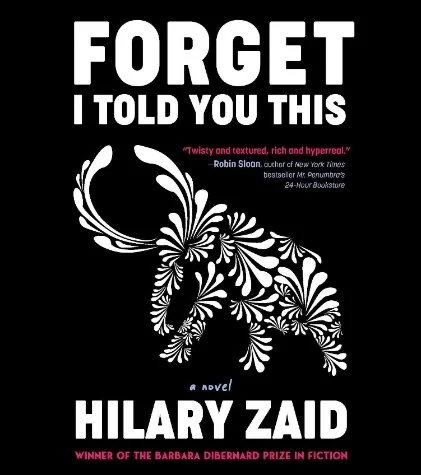

Hilary Zaid, Forget I Told You This (and new books by Joan Silber, Marisa Silver, and David Haynes)

/Upstairs, twinkle lights garlanded the doorways of makeshift lofts, thin walls draped with heavy carpets to muffle noise. The floor felt solider up here, at least, and I was only half-alarmed by the sight of a piano—a black, squat baby grand, like my mother’s—under the scales of a wire-frame dragon. Around us, pressing close against our skin, all the warmth of the warehouse gathered like a thick blanket, heavy with weed, cut with the sharp tang of electricity and Blue’s midnight scent.

She led me into a glowing doorway, a tiny improvised jewel box just big enough for a small nightstand and a double bed. Chinese lanterns, gold and red, clustered in the high corners, the golden light heavy against the flimsy walls like ripe fruit bulging against a paper box. In the window above the bed, night had flattened itself against the pane. The room didn’t have a door, just a curtain—velvet, like the curtain on the back room of Crimson Horticultural Rarities. The velvet curtain, the close, warm smell of her perfume, the light seeping like golden liquid from the lanterns—all of it brought his words whispering again into my ears: Everything depends on you.

Hilary Zaid’s page-turner of a second novel, Forget I Told You This, focuses on Amy Black, dislocated by her not-very-empty nest after her son has left for college and her high-needs parents and brother have moved in with her, and just at the time of year when she’s reminded of Connie, who broke her heart years ago. Amy is face blind but has a gift for paying an obsessive, jeweled attention to all the other details of the world. Her story is also both realistic and magical – she’s an artist of letters, a scribe who, in writing a letter for a stranger, gets drawn into a plot involving dangerous men who want something very specific from her. She’s longing for an artist’s residence at Q, a world-dominating social media company, and her forays into the company raise intense questions about AI and surveillance and also give her a glimpse of a rare, gorgeous manuscript. The pressures she’s under create a high drama and also dreamlike plot.

In the paragraphs above, Amy’s spending the night with a woman she’s met online, not long after her first scary encounter with the men. She climbs up a set of terrifying warehouse stairs towards pleasure, a Jewish Scheherazade taking us into an unnerving cave, high in the air. The immersive imagery presses in, conjuring the smells of weed and perfume, the warmth, the glow, the sense of possibility. Amy and Blue only know each other through their online identities: this moment may never be repeated, since Amy can’t recognize anyone through the clues that most people use.

She’s middle-aged but feeling her possibilities, as an artist, as a person, as if she were re-entering her teens, but with a knowledge of herself and the world that both gives rise to doubts and also lets her take big risks. The rich, densely poetic description captures her danger, along with a magical sense that anything might change for her now.

Going through the book again has been a reminder that every paragraph here is marvelous. How perfectly worked, how beautiful. I first read the novel not so long after it came out, two years ago, and find myself thinking about it again surprisingly often, thinking about sharing it with you all, unable to choose a paragraph or passage to read. Everything feels dependent on everything else, and to choose one thing means letting all the rest of it go for now. Tangibility and beauty matter all the way through this novel, in moments of connection and also when it’s frightening. The way men use power. The perils of AI, data privacy, and corporate dominance. Her first book, Paper is White, took on both marriage equality and the legacy of the Holocaust (the protagonist of that book is an oral historian of survivors).

It would be possible to write books like these without making them gorgeous, but I think it’s helpful to have presents to give the reader. I’ve written before about the difference between dark and bleak writing in “The Pleasures of Hell” for the AWP Writer’s Chronicle (originally it was a lecture for the Warren Wilson MFA program for Writers.) And, as increasing numbers of writers talk to me about difficulties in writing during emergency times and trying to figure out whether and how to write about the emergency itself or what the hell to do, I want to quote a piece of my essay here.

As writers, we may have our ideas of what our work is about, but it will get loose from our own “moral demands” or preconceptions. Even if a poem or novel has a moral or political agenda, it will – at least if it is a work of art – make unsettling emotional or aesthetic discoveries that complicate its project. These books are never going to be pleasing in a sunlit-Bonnard-afternoon-tea-in-the-garden fashion. But a fictional or poetic world that’s stubbornly, unremittingly dark, in which no good thing can happen, and every character commits or endures horrors, tends to wind up as either comic – intentionally or unintentionally – or unreadable. And no matter how drastic the situation we want to hold up to the light, we have to offer readers a reason for walking into our world, then more reasons to stay in the world once they get inside. A very few books may exist that, in a spirit of stern purity, offer the readers no pleasure whatsoever, but most of us have never read, or at least never finished, one of these works.

A book that depicts some version of hell may be dark without being bleak. I want to consider the difference between “bleak” and “dark.” A hell can be dark without being bleak, though this is no calumny against all the gorgeous and bleak literary worlds out there, the depictions of real and metaphorical hells. Sometimes a work of art about hard subjects can and should be bleak.

In a bleak poem or work of fiction, an individual character may or may not survive, but the world in these books is always, in some way, a prison. The author controls the work’s tonal palette, generally keeping it in the gray range. A bleak work can be hysterically funny, like Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape or Waiting for Godot, but it will be a despairing humor, if so.

[There’s more of this, including some Paul Celan, but that’s another story…so skipping ahead!]

In William Trevor’s Love and Summer, hell is the ultra-realistic, gossipy, unspeakably narrow Irish town of Rathmoye, and the book a story of a love that can’t quite happen, a past that will never release its people to a better future, duty locking down any possibility of true life or pleasure. There is an ashy quality to the characters’ lives, just like the lives in Cormac McCarthy’s Road, in which – though McCarthy allows a temporary survival for one of the book’s two major characters – the world is lost to a gray post-apocalyptic life in which nothing grows, humans roam in a state of constant, cannibalistic semi-starvation, and survival is a bitter parental duty, the goal being to last as long as possible, to protect your only child even as you become less and less certain of how it would be possible to go on thinking of yourself as one of “the good guys.”

A dark, but not bleak, work tends to have a much broader tonal palette, contrasting the dark images or events with playful or comforting ones. It also tends to have more major characters, more of a sense of the group, of people having wildly divergent fates. Such a work is definitely more likely to show a world that, however terrible, has exuberance and even hope. A completely different post-apocalyptic hell, one both bright and dark, comes from one of McCarthy’s precursors, Octavia Butler: Parable of the Sower, told in the extremely spare language of the teenage narrator’s diary, with a vividly populated world. Though society is in complete disarray, there’s a believable mix of rapacious and altruistic people, as well as the contrasts of the evils of drugged-firestarters and the potential of corporate slavery and the hopeful signs of continuing humanity: hidden community gardens and cautious alliances of strangers. The novel could almost seem an answer to McCarthy’s carefully controlled tonal range of grays and absences if it hadn’t been written more than two decades earlier. The teenage narrator’s prophetic gifts, and her Earthseed religion, lead most of those she gathers to become her hopeful followers on a fraught journey north. Butler’s dystopia still retains, however marginally, poetry, imagination, food, sex, and potentially irrational moments of kindness.

Zaid’s work is heir to the kinds of questions Butler poses, though she is very different as a stylist. Forget I Told You This insists on the human scale and the possibility of sudden, unexpected change. But there are also hiding places in the book, part of what’s so delicious in the paragraph above: “She led me into a glowing doorway, a tiny improvised jewel box just big enough for a small nightstand and a double bed. Chinese lanterns, gold and red, clustered in the high corners, the golden light heavy against the flimsy walls like ripe fruit bulging against a paper box.”

High above the world (or, okay, the warehouse), there’s a jewel box, a place for pleasure, a place to escape from loss, confusion, into somewhere glowing and golden, a bed just large enough for Amy and Blue. The walls are flimsy and won’t last, the fruit will eventually go from ripe to rotten if it’s not savored right away. There is only this moment.

She brings this sense of slowed intensity even to fraught moments, as in the passage below, a grand, high-stakes party with a lot of risks for Amy (and the world). Zaid’s sentences wind through the crowd, languorous, intense, full of exuberant, celebratory invention:

The main hall was vast, high ceilings and arched windows, ornate moldings and marble steps in their flaking shabbiness evocative of that greater Age of Rail. White pillar candles burned everywhere in great organ-pipe configurations. The thick, warm smell of wax bleared the air and warmed it. People milling at high tables drank blue liquids from real glasses. Pastry flecked dark beards and wide cravats. Everywhere, people had dressed for a fin de siècle Sunday in the Park of Frozen Brimstone: women wore high bustles and straw hats; men wore frock coats and monocles dangled from chains; but their smiles unveiled shining fangs and all their eyes were blue as veins. They were drinking and laughing loud, roaring, while blue-sequined Satans with forked tails delivered cool blue canapés. So many shades of blue but the one I wanted.

At a table near the door, I found a scattered stack of temporary tattoos: the nude suspended inside a leafy O against a spangled sky. Press on with damp sponge, the instructions on the back read. Wash off with soapy water.

I wandered back outside toward the old ticket window under the graffiti-splashed trestles, to a dank little room where a large metal sign offered Fountain Souvenirs Cameras Films Sundries in sturdy, early mid-century block capitals. Among the crowd, I felt more displaced than ever, the costumes and the colors and the laughter accentuating my own oddness, my blindness. But, down the old refreshment window, I could imagine myself somewhere else, sometime else, alone at the start of a journey.

I stepped into the cool, abandoned space where travelers once bought newspapers, peanuts, and popcorn. The room echoed with dripping water, though I could not see water anywhere. Light spilled from the farther doorway and I followed it.

A floodlight blazed up the tiled phone vestibule, the telephone long ago ripped from the wall; at an eagle-gilded lectern stood a woman with dark, radiant skin, and a halo of hair spangled with silver glitter. She wore a shimmering white robe on which great, feathered wings had been mounted at the shoulders. From the darkened door behind her podium, I could hear laughter, echoed voices.

“Settle down, y’all!” she yelled out without turning around. “I’ll be there in two freakin’ seconds.” Then she pulled a bottle of Perrier from under the lectern, and with a hiss brought the bottle to her lips until all the water was gone. “Whew.” She wiped her mouth with the long sleeve of her robe and murmured, “Just let me find the damn script.” She shook her head and a cloud of glitter materialized around it before shimmering down into the dusk. “Everyone always has some new plotline to add to the damn script.” With a huge sigh audible over what sounded like the hammering of metal, she tucked the bottle back out of sight and began to turn away, one big wing brushing the side of the lectern. “And tonight is supposed to be a party.”

I stared a moment too long. Before she stepped into the darkened doorway, she spotted me and turned back.

“I’m sorry—” the Archangel glittered coolly on her perch, eyeballing my black skirt and top. “Are you lost? Witches are meeting up on the train platform—” she shook her robe up to her elbow and tilted her wrist awkwardly toward the light, revealing a thin, gold watch— “fifteen minutes ago.”

Amy is still displaced but can imagine herself “somewhere else, sometime else, alone at the start of a journey.” She’s stepping out of the crowd, going backstage; so much of this book gives the pleasure of going backstage and into rooms we would never have known existed, full of remarkably imagined treasures, some handmade, others acrobatic conceptual structures. The Archangel has lost the script, and there’s some new plotline. Amy, out of place everywhere, mistaken for a witch, is at home in the act of paying very close attention.

In an interview for I Heart SapphicFic, Zaid said, “There are a lot of Wonka-like elements to the world created in this novel, magical-seeming places around my hometown of Oakland, California, and they are all actually real places. I loved writing those scenes and having fun making the ordinary feel magical.” So, some magic in the middle of everything, for the character and for the reader. Nothing is ordinary right now. But the extraordinary ordinary feels like a place to go for hope, comfort, restoration, and courage.

News from MPP Contributors

This is a totally stellar month for new books from former MPP contributors. Joan Silber’s Mercy and Marisa Silver’s At Last both publish today! Congratulations to Joan and Marisa, two astonishing writers, doing some of their most intense, extraordinary work ever.

“Joan Silber’s sweeping yet intimate novel traces the delicate patterns by which others, often from afar and unknowingly, may determine our innermost longings and even our fate. Mercy is a profound, gorgeously written reflection on identity, friendship, and love. A book that keeps echoing long after turning the last page.” —Hernan Diaz, author of Trust

“Here’s the magic of Marisa Silver’s books: they capture, beautifully, not only entire lives but the complex histories that pulse through our country. At Last is, quite simply, her best book yet.” —Paul Yoon, author of The Hive and the Honey

And then, in just a few days, on September 9, David Haynes’s Martha’s Daughter: A Novella and Stories, another fierce, brilliant book, will be published. Here’s what Natalie Baszile, author of Queen Sugar, has to say about the book, and I completely agree: “David Haynes is a master storyteller—intelligent, insightful, generous, and wickedly funny. Martha’s Daughter is a delight from beginning to end.”

My News

This summer, thanks to the meticulous generosity of Four Way Books, Rowan Sharp gave me four rounds of page proofs. They also did my copy-editing, so that off and on for the last couple of years, I’ve had the chance to be part of a prolonged, warm, insightful conversation that went all the way from my editing with Ryan Murphy through these stages with Rowan (after, of course, a lot of truly great help from early readers). Also this summer, I had the chance to teach a gifted, highly engaged group of writers in another intense conversation, on voice and style, and I took an illuminating book publicity intensive class with Leah Paulos of Press Shop. So though my sweetheart and I went to the beach exactly once this summer, with the family, for their birthday, and then took a few walks at the citified edges of the SF Bay nearby, it was a beautiful summer in our personal lives. Otherwise, the hellscape continues. I like the theory that it’s starting to come apart. There’s this photo of a chunk of the Berlin Wall that I look at sometimes. You never know when it’s going to fall: we’re always trying to find small ways to be part of making that happen. And meanwhile, trying to keep reading and remembering to pay attention to the small riches all around us.