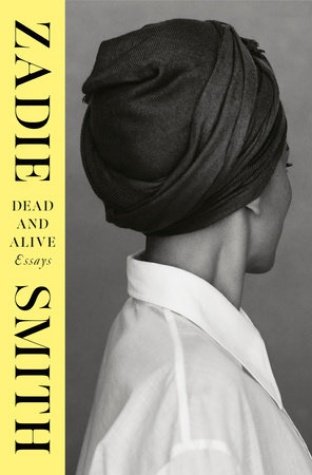

Zadie Smith, Dead and Alive: Essays (plus great books by friends and cozy escape fiction)

/Here is a false memory: one of my writing instructors once said, “You do not need to find an organizing principle for your work. You are the organizing principle.” This was enormously freeing—we could write fiction, poetry, essays, plays, articles; we could return to the same material or styles over and over; we could try out wildly new voices. This would not be evidence of uncontrollable messiness and failure to understand our own projects as writers, not to mention our own purposes here on earth. This writer, at that moment standing in the oracular spot at the front of the classroom and therefore speaking The Truth, seemed to be saying that it was fine to write whatever came to us: our own obsessions and projects would inevitably emerge. In fact, this isn’t my memory at all, but belongs to my spouse and writing partner, Ron, who once took a weekend workshop with Kate Braverman. Ron told me all this more than once, and I ate that memory and made it my own. Thinking of the writer as an organizing principle, and also as a person who will hoover up everything around them and make it theirs, is one way in to reading Zadie Smith’s complex, sad, gripping new collection, Dead and Alive: Essays.

She has divided the book into five parts: “Eyeballing,” “Considering,” “Reconsidering,” “Mourning,” and “Confessing.” Because the organizing principle that is Zadie Smith is unstoppable and full of tendrils, the groupings are loose, with art more or less in “Eyeballing,” political essays more or less in “Reconsidering.” Then there’s “Mourning,” where Smith remembers her relationships with her literary heroes (including Hilary Mantel, Martin Amis, Toni Morrison, and James Baldwin). Throughout the book, she mixes the analysis of art, bodies of work, politics, received ideas in every realm, and the contemporary mediated approach to life. She knows, as she does this, that people will misunderstand. She doesn’t have a “so what” attitude about any of this, but doggedly, courageously pushes forward even without any absolute certainty that she’s in the right or that it’s possible to be in the right. No sound bites or reels, just a mind at work on the page. Even in the most personal essays, she equivocates without giving way. She is ambivalent and nuanced but not uncertain.

“The Fall,” in “Confessing,” is one of the few essays that might be purely personal, if Zadie Smith ever wrote anything purely personal: the story of how she fell out of a window in her teens in a very dark time, when she’d been unrequitedly in love with a dear friend for seven years and had once again tried to convey this to him. In writing about all this and investigating what she identifies as a central topic (“volition”), she wrestles with how she could have been so happy and so sad, self-destructive but with no conscious intention of dying. Being Zadie Smith, she’s profoundly driven to give us context, to create an opening for us to understand who she was then, how she saw it, how she sees it now:

Back-story: I lived in a world of pure Prince then, and also in a filthy pit of my own creation. Sometimes when I am ranting at my own children about the state of their rooms, I suddenly remember what I used to think whenever my mother came in and tried to complain – over the blaring sounds of Prince’s ‘Sexy MF’ – about the bowls of old food stored under my bed, and the cigarette butts put out in the old bowls of food, and the candles I liked to burn and melt into the damp carpet. (Sometimes, if I got bored of a glass of water, I would just pour its remnants out onto the floor.) Yes, when my mother was making her case against me, this is what teenage me was thinking: You poor woman. If only you had a life of your own! What a pitiful existence is yours if the only thing you can think to do all day is worry about these petty ephemera! (Teenage me was reading the dictionary.) She could be standing right in front of me – perhaps holding a Brie sandwich with five cigarettes put out in it – having just come back from a long day as a social worker, dealing with the kind of children who did not get Brie to put into their sandwiches, and could not scream GET OUT OF MY ROOM, for they shared that room with their family. And still I would look at this single-parent, hard-working, immigrant mother of mine and think: Jesus Christ, woman, get a life. Every now and then, though, I took genuine pity on her. Genuine pity meant not changing any of my behaviours but rather lying and saying that I had. This particular April I’d sworn to her I wasn’t smoking. Therefore stolen cigarettes. Therefore windowsill.

Oh, what fabulous, disgusting, memorable details! That juxtaposition of Prince with the old Brie sandwiches full of cigarettes. Smith is judging her teenage self here so hard I’m reminded of Great Expectations and Pip’s retrospective agony in looking at his past self, his inability to value Joe Gargery, his blacksmith brother-in-law, as Smith could not understand her mother. She expresses even her pity by lying, and her pity is nothing like as vivid as her contempt. Pouring out water on the floor! Very appealing that she’s willing to expose this, while not exposing a single detail of what her own children are doing in their rooms (many contemporary writers would go ahead and add that in).

Smith’s mixture of piercing judgment and human understanding show up in how she examines herself, art, and the world (including the very hard political convulsions we’re in the middle of—Trump appears 19 times in these pages, and even Musk makes an appearance, though he no longer even seems like the right oligarch to focus on, but could well be by the time you read this, because who knows what will happen on any given day?). This mixture also feels key to her fiction, which functions by the organizing principle of Smith’s consciousness and awareness of all the facets of consciousness. (I’ve been rereading and teaching her novel On Beauty again—I meant to just skim it, but I sank all the way down into it and engaged in classroom conversations that revealed aspects of the book I’d never seen).

Here’s a passage from “Conscience and Consciousness: A Craft Talk for the People and the Person,” which started as her “very last Craft Talk,” which she gave “over Zoom, on 20 May 2021 to students in NYU’s Creative Writing Program.” Much of the essay focuses on James Baldwin. She also tackles craft as related to consciousness and identity:

I think of the craft of creative writing as a rare opportunity to communicate something of consciousness. It can of course do many other things. It can speak of history and politics, argue and debate, lecture and analyse. But many other kinds of writing can do all that. The communication of human consciousness is something only creative writing can do. That is what I love about it. When I am writing I am trying to convey the rhythms, operations and movement of my mind in the face of all-that-there-is. What I notice rather than what I am told to notice. What interests me rather than what I am instructed to be interested in. How I experience colour, or light, or birds, or other people, or the concept of race, or a table, or a dog, or history. I can use one character or a hundred to convey these impressions. I can write it in the first person or the third. Write it in a novel or a play. I don’t consider these formal differences as important as the unit in which I do it all. Ideally, when I write a sentence there should be something about it that is mine alone, a particular rhythm and shape. It should have a distinct vibe above and beyond its manifest content. I think all the writers I love have this distinction of distinctness. I can tell a James Baldwin sentence from a Toni Morrison sentence half a mile away, and not because one sentence is about Harlem and the other about Ohio. They could be describing the very same child standing on the corner and I would know the difference. Their quality of attention is different. They move through my brain a certain way. To use an inelegant twentieth-century metaphor, they take the software of their consciousness and run it through the hardware of my mind.

But that metaphor makes it sound easier than it is. What becomes clear once I sit down to write is that my first obstacle is language. As a writer, you want to make the language fresh and new, but you have to make use of the very same toolkit, language, with which people have previously ordered nuclear attacks and screamed at children. Far from being my intimate possession, the language I’m using as raw material is shared by millions in my nation and used for all kinds of banal pursuits like ordering a burger or asking where the toilet is. It’s mutilated in adverts, butchered by politicians. And out of this impure material you hope to make your own sentence? That’s just the lower half of the problem. The top half is the fact that this very same software has had some really rather impressive former users. George Eliot. Tolstoy. Kathy Acker. Teju Cole. To name four. What can you possibly do with it that has not already been done?

That’s not, of course, the end of her thoughts about what can be done with language. This is an essay that one could read many times, as her novels can be read many times. A couple of friends and I went to hear Smith speak a few years ago in an enormous auditorium. We had arrived so early (hours ahead of time: we ate our dinner in line) that we were very close to the stage. And there she was. I cannot tell you a single one of the many brilliant, warm, self-deprecating, complicated things she said on that occasion, because I was so stunned to be right there, trying to listen, trying to stop analyzing my own inability to listen because of my dazzlement. Still, I came out feeling like a slightly different (maybe better) human being and writer. And it’s moving to see her just as dazzled by Hilary Mantel or James Baldwin. I keep teaching Smith’s work to writers because she astonishes us, and it feels as if she’s always addressing both a vast lecture hall and each one of us, personally, individually.

A Month in Reading

Some other wonderfully human, inventive, and surprising books I read this month were by friends, including Ann Packer’s Some Bright Nowhere (madly love this novel and also found Oprah’s book club podcast, very moving, though I’m glad I watched it after reading the book) and also Marianne Villanueva’s mind-blowing stories in Residents of the Deep. Also, possibly as a result of reading a lot of Rebecca Solnit and Heather Cox Richardson and doing resistance trainings, etc., I have binged some funny, cozy books on love, baking, and chosen families: Sangu Mandanna’s A Witch’s Guide to Magical Innkeeping and The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches and Alexis Hall’s Rosaline Palmer Takes the Cake and Paris Daillencourt Is about to Crumble (both from the “Winner Bakes All” series).

My father’s not-so-secret fantasy of an alternate life was to run away and become a woodcutter who’d live in a hut in a forest (he was a professor of health psychology and so profoundly a mentor that they named a room after him at his university: at its dedication, former post-docs from all over the country, who were all doing wildly useful things, showed up to say what his work had meant to them). My secret (until this moment) fantasy of an alternate life is as a writer of witch romances. And, given my fascination with narcissism and the ways we use our power over others, I’ve been obsessed with vampires since early teens and read a horrifying number of both good and awful vampire books. But my writing mind doesn’t work that way, and I’m fine with writing the books I actually write. Literary fiction feels like my real home, and I’m glad to go back to it after reading escape fiction (or those pop sociology books where the writer carries out some experiment in self-reinvention with lots of entertaining research).

I’m also glad to teach in a circumstance where people write not only literary fiction, both speculative and realistic, but every other kind of fiction, and sometimes nonfiction, for every kind of reader. I like being able to use in teaching not only what I learn from more literary works but also what I learn from popular fiction about wish fulfillment and how these books might also give us a chance to inhabit meaningful explorations of values and human life, c.f. Mandanna and Hall. (Though let’s not get into the neuroticism of every single thing in life having to somehow be of use to other people or the world.)

My News

Speaking of teaching—my upcoming class is a six-week, not-for-credit online course starting in January: “Lightning in a Bottle: Crafting Flash Fiction and Nonfiction,” through Stanford Continuing Studies. The emphasis is on the live/recorded 90-minute Zoom class, but there’s an asynchronous piece as well for people who want to post their flash pieces. Here’s more information, including the syllabus. Registration opens on Dec 1. at 8:30 am PT, and I never know whether courses will fill up instantly (7 minutes is my record) or stay open for a while. So if you’re interested, please mark the calendar.

Otherwise, I am turning from my next novel (like any writer, I want to live in a burrow with my next novel) to finishing some essays in progress. And meanwhile, we’re getting ready to host that complicated, problematic holiday, Thanksgiving, for (owing to health things) a currently unknown but noticeable number of family members. Can we call it a Harvest Festival? In one recent year, there was a rule that those of us who wanted to talk politics needed to go outside on our hosts’ porch. Like a smoking section, but more of a shouting section. Not that we disagreed. That only happens in primary season.

Whatever you have planned, I hope it brings you meaningful memories, delicious food, and deeper more nuanced relationships. Or at least, for the writers among us, interesting new material. Happiest possible holiday!