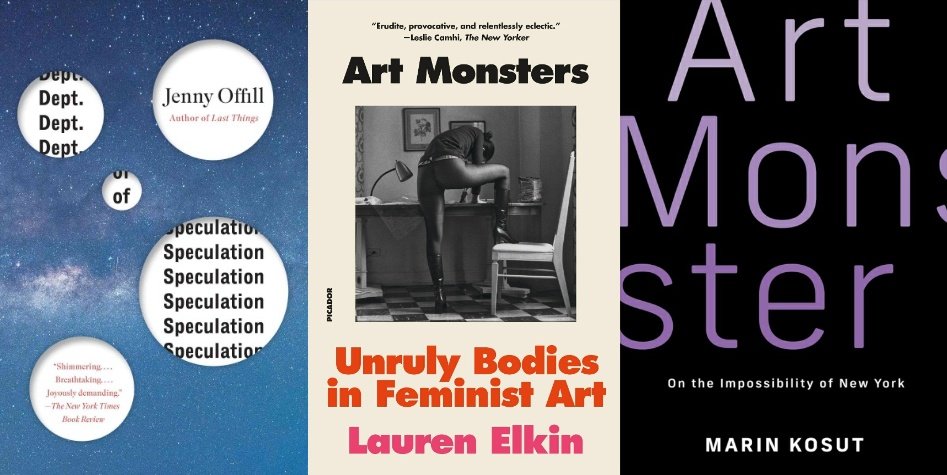

Jenny Offill, Lauren Elkin, and Marin Kosut, On Being (or Not Being) an Art Monster

/The holidays are over, like a dream, and “real life” has started up again, like a very different dream. Did we do what we meant to? Or are we now trying to corral ourselves with goals, intentions, and to-do lists? No more treats! Get the work done! Many (most?) writers I’ve worked with spend so much time on the pleasures and requirements of daily life or the more stringent demands of caretaking that they have trouble believing they are real writers who can finish books and get them to their readers. I’m with these writers: family, friends, teaching, and community give me most of my life’s delights, bafflements, and worry. We want a full, rich life, don’t we? What could matter more than hanging out playing the Once Upon a Time card game with friends and family around a hospital bed, or serving on committees, volunteering, engaging in political action? But is there a small (or large) part of us that imagines a life of total, ferocious devotion to the work we feel we need to do? That longs to become what the narrator of Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation thinks of as an “art monster”?

Here’s the opening of Offill’s short story version (“Magic and Dread”) in The Paris Review, where I first read it:

My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his umbrella. Véra licked his stamps for him.

Each day when he left for work, I would stare at the door as if it might open again.

The only thing the baby liked was speed. If I took her outside, I had to walk quickly, even trot a little. If I slowed down or stopped, she would start wailing again. It was the dead of winter and some days I walked or trotted for hours, softly singing.

What did you do today, he’d say when he got home from work, and I’d try my best to craft an anecdote out of nothing.

I read a study once about sleep deprivation. The researchers made cat-size islands of sand in the middle of a pool of water, then placed very tired cats on top of them. At first, the cats curled up perfectly on the sand and slept, but eventually they’d sprawl out and wake up in water. I can’t remember what they were trying to prove exactly. All I took away was that the cats went crazy.

Those tiny islands of paragraphs. The numb, sleep-deprived associative quality. The no-time-to-waste clean prose. Véra licking the stamps. The perplexing puzzle of handing over a huge part of our lives to caretaking—physical, emotional, or psychological. So Offill jumps from the art monster fantasy to the sometimes lonely and demanding, but deeply rewarding, position of mother of a newborn to those cats losing their minds. The form plunges readers into dislocation.

When I first read Dept. of Speculation, I couldn’t wait to introduce it to other writers and showed up at my next MFA residency to find that multiple other faculty members or our grad students had the same idea. A little club. Finally! Art monsterdom! We would break all expectations, whether our own or anyone else’s. And maybe that involves breaking the forms. Offill happened on the narrative strategy of Dept. of Speculation when she was writing what might have been a domestic novel about having a baby and some marital trouble, a subject that seems infinitely intriguing but not plotty or “high concept.” But it didn’t capture what she was after. So she found this structure, which took both artistic and emotional daring. Offill has talked about finding the form for the book in several places, including a conversation with John Self for Asylum:

Dept. of Speculation deals with everyday life but is unusual in its form and content. (“She acts as if writing has no rules.”) Can you tell us something of how the book came about?

I had written a more conventional novel about a student who had an affair with her professor and later married him. The book was from the POV of the second wife and of her stepdaughter. I worked on it for years, but there was always something leaden about it. What I wanted to write was something darker and stranger, something that spoke more directly to the collision of art and life. Eventually, I screwed up my nerve and dismantled that original novel, keeping only a few tiny things.

I read a lot of poetry and non-traditional fiction and for a long time I’d wanted to write in a more experimental vein. Dept. of Speculation was the result of finally writing exactly the way I wanted to without worrying about whether anyone else would like it. (That anyone did was a thrilling surprise.)

The book’s appearance is also unusual: paragraphs appear as separate sections surrounded by white space (you describe it as “maddeningly formatted”). Each paragraph has a stand-alone, aphoristic quality. Was it important to tell the story in this way?

The white spaces in the novel are meant to be resting places for the reader, stop-offs before the wife wheels off in another direction. I thought it would be overwhelming to be in her head in a linear, uninterrupted way.

The aphoristic quality developed because of that constraint, but I liked it and decided to heighten the effect. One of the things I was interested in was making the seemingly trivial domestic moments have the same weight as the more obviously philosophical ones. The aphoristic style helped me to put the mundane and the sublime fragments on the same plane.

There are a lot of ways, of course, of keeping a more linear novel from being leaden: inventive events and plot turns, intriguing interiority, or possibly characters with very different desires and world views who find themselves in the same family, workplace, or marriage. Maybe there’s something about the juxtaposition of art monster and domestic life that trips the circuits of linearity; art monsterdom and domesticity can’t inhabit the same space.

Domesticity can exist as a fantasy (hi, tradwives!) but is mostly rooted in particularity: changing diapers, scrubbing the sink, telling silly jokes while watching TV, everyone under the same blanket. Art monsterdom is an entirely different fantasy: the illegal squat, the twelve-hour workdays, most of all the cost to everyone else. Rilke didn’t go to his daughter’s wedding and refused to let her stop by on her wedding trip for his blessing because he didn’t want his writing interrupted. And what about those artists willing to let someone else give over the major part of their life and attention to typing their manuscripts or licking their stamps (even while noting that gender and power play a big role in this, I don’t want to focus on those who succeed in being art monsters but those who perhaps feel they ought to be art monsters or at least more art monsterish).

This summer, an artist friend and mentor and I agreed that we were going to be art monsters (this didn’t last, at least for me, but felt wonderful at the time). My friend has a long history as an art therapist, teacher, creator of new fields and her own art and writing has a mysterious, bewitching magic. She sent me to Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, which is so much about the collision of art and motherhood and which chases its ideas in every direction and across different forms (and which refers repeatedly to Offill’s novel). Elkin writes, in defiant longing and celebration, about an “aesthetics of monstrosity”:

Pregnant, the art monster idea nudged me not towards vampires or zombies, but into art made of the everyday experience of having a body. Towards monstrosity as a strategy for making work that reaches us viscerally, which overspills its container, and threatens, in response, to make us overspill our own. I was drawn to feminist artists who interrogated notions of appropriateness and excess, breaking down and rerouting expectations, imagining life outside the binaries of gender, cracking open our ideas about beauty to show that it is a quality that is not diametrically opposed to ugliness, but one that sits next to it, and often overlaps with it. An aesthetics of monstrosity would not be about countering beauty with ugliness or vice versa, or even adhering to pure categories, but about re-aestheticising the aesthetic, bringing touch and feeling back into our encounters with art, centering the body and its viscerality, liberating it from patriarchal and normative control.

Elkin considers how this might blur categories, what it means “to take the monster out of the realm of morality, into some more subtle, harder-to-define ethics that is also an aesthetics.” Like Offill, she feels restricted by any kind of conventional form. She is bringing together all these connected ideas in an embodied rather than linear way. Rather than following the traditional academic path of setting out an argument and supporting it, she wants to break boundaries across disciplines and time.

Intrigued and perplexed by the book and trying to find out more, I accidentally came across Marin Kosut’s Art Monster: On the Impossibility of New York. This multidisciplinary work spirals out into the romance and reality of life as an artist, grounded in Kosut’s experiences as artist, teacher, and curator, as well as those of other artists she knew (Kosut also credits Offill for the term and her title). So many topics and byways here, including ideas about what it means to be an artist in a late-stage capitalist world and a gentrified New York. Kosut sets out her understanding of who is, and who is not, an artist and what it means to make art (and to be an art monster). Here’s a very short and nonlinear chapter (most of the book is far more analytical):

Artists I Knew

The artist who made a square helmet out of plywood that looked like a 1960s robot head and wore it to basketball courts and tried to join pick-up games while his girlfriend filmed.

The artist who secretly lived in her studio, peed in a white plastic five-gallon bucket and washed her bras in the bucket.

The artist who painted bananas and wheel chairs, who was mainly interested in cats as subject matter.

The artist who had an aneurysm and didn’t die, who taught himself how to draw while he recovered and the swelling receded.

The artist who made a full-size replica of herself and brought the doppelganger to Sears to take a family holiday portrait with it.

The artist who painted tree stumps, who never watched or read anything to avoid being influenced by the culture.

The artist who used the lexicon of black metal and death metal imagery to sew crowning paintings, because giving birth is metal as fuck.

The artist who choreographed a human foosball game next to an abandoned warehouse, while a chef roasted a pig behind the goalpost.

The artist who preferred to play inside an attic room and a hidden crawl space as a kid, who spent six months building an elaborate two-story replica of his childhood home inside a gallery.

The artist who went undercover as the heir to a fashion dynasty for a year, who went to New York celebrity parties and posed for pictures with Hillary Clinton and Puff Daddy.

The artist who collaborated with his indigent father to attempt to assemble a 13,200-piece jigsaw puzzle depicting The Creation of Adam as a three-week public gallery performance, who unexpectedly died five years later, at the age of thirty-three, within a year of his father’s death.

The artist who threw a painting in a field, found it a year later and said it was better and it was finished.

The artist in me who was buried, and the artist who raised her to light.

These defiant islands of summary seem to offer so much clarity, as if someone can capture the essence of a big messy ongoing art project in a marvelous sentence (or paragraph): so many potentially nonart things that can still be art. But then this chapter’s immediately followed by a much longer, more detailed chapter on “Artistness,” an elegant rant about artists and creatives that winds up trying to fill a gatekeeper function as to who gets to consider themselves to be an artist, a task somewhat sideways to Kosut’s celebrations, in both form and content, of the act of breaking free of the expected. But then she’s not after consistency. She makes her points and then goes in another direction, maybe contradicting, maybe amplifying, with some wild, deeply researched specifics as materials. She also felt that “a standard scholarly book based on ethnographic interviews” was too formulaic (she talks about this in a conversation with Mary Karmelek for Hyperallergic.)

All three of these books wrestle with the nonlinear and unexpected. They’re full of ambivalent longing. The mother in Dept. of Speculation has no desire not to be a mother, but she’s also baffled by how hard it is.

Often what people—mostly, but not always, women—mean by being an art monster is more or less allowing oneself to live the life of an artist. Finding time to work by skipping other things. Believing in something, even if not one’s own abilities or promise, enough to keep going through the hard times. Before the world believes in you, after the world turns its back on you, or whether the world ever knows that you and your art exist. Not the Nabokov level of art monster but a person who has ideas or a desire to make something and creates some room for that to happen. And not via grand New Year’s resolutions or unrealistic page count goals or dreams of getting a lot of worldly validation, but through figuring out what we’re interested in learning and going back to the studio or desk pretty often.

When we lose the thread—maybe because we got temporarily stuck in our ideas and took a break or because we’ve been spending a lot of time with family, friends, and community—we might, without guilt or self-recrimination, give ourselves a few potentially challenging not-so-productive days to find that thread again. Living in the unromantic middle zone. Not as an art monster but also not giving up on being part of the whole long history of people making something new in the world and following their own curiosity to see where they wind up and what comes of it.

My News

The upcoming launch of Marriage to the Sea is getting a lot of time and energy, of course. Now just over two months away. Any time you publish a book, it’s like throwing a big party: right now, I am still setting up the table and then running out to do final errands. Over the holidays, there were some hard things but also holiday fun with friends and family and different communities. It rained like crazy, and the full book manuscript I was going to work on is delayed in coming in, so I had the chance to read several intriguing novels not completely unrelated to art monsterdom (Katie Kitamura’s Audition, Hannah Pittard’s If You Love It Let It Kill You, and Solvej Balle’s The Calculation of Volume I and part of II). And then a couple of beautifully written books that also expertly fulfilled romcom and thriller genre requirements: Alison Espach’s The Wedding People and Liz Moore’s God of the Woods. I’m glad that Nicole Holofcener will be writing the movie version of the first of these: it has so many good, weird tangents. Ron and I have been watching Midnight Diner: Tokyo Stories, The Traitors s3, Hjem til Jul, and Astrid et Raphaëlle.

We have no idea what lies ahead this year. But I think a good intention, in art, in our lives, in politics, might be not giving up no matter what. Holding onto that as we embark on all the unknowns. Looking forward, as always, to hearing from you about how you are and what you’re up to: one of my favorite parts of these notes is the comments and letters from you. I appreciate you reading these thoughts and am curious about your own relationship to art monsterdom.